If there is one thing I’ve noticed over the course of my career it’s that project governance artefacts are often fragmented to the extent they are like straws thrown on the floor. The nature of the project and my role within it can vary significantly but this can be a common observation.

The better way to look at the governance artefacts of the project is they are the grammar that builds a story that can be told as a powerful project narrative.

Challenge, Reason and Solution

Let’s envision this problem as the challenge, the reason for it and the solution.

The challenge is the leadership of the project is impacted because the project isn’t using key governance tools to tell a powerful project narrative.

The reason is the governance artefacts of the plan, RAID log, status report and status meeting aren’t being constructed with the single goal of providing that powerful project narrative. We go into what this can look like in fragmented governance artefacts.

The solution is to focus the artefacts around telling the powerful project narrative across the project’s life. How to achieve this is the focus of this post.

Fragmented Governance Artefacts

A random selection of what fragmented governance artefacts can look is laid out below: –

- The status meeting is not compelling to the stakeholders

- The status meeting is not focused on the narrative and the future

- Status reports don’t tell a story individually and across the project

- The RAID log is full of neglected, confusing and forgotten statements

- The plan is often out of date

- The plan is obscure and doesn’t tell the story of the journey to the end

- It’s challenging to reconstruct the events of the project easily

- Governance artefacts aren’t used in the project conversations at all

- The artefacts aren’t better than the sum of their parts

- The project always seems to be about immediate, tactical problems

- The focus is on internal corporate governance, not project stakeholders

The artefacts used to weave this powerful project narrative are tied to the project manager’s options for leading the project.

Delivering the powerful project narrative

So, what does delivering a powerful project narrative look like? We can draw analogies with grammar, story and narrative. The grammar is the structure and the language of the project, the story is the account of the people and the events and the narrative is how we choose to tell it which is where the power lies.

We can align these elements with key governance artefacts.

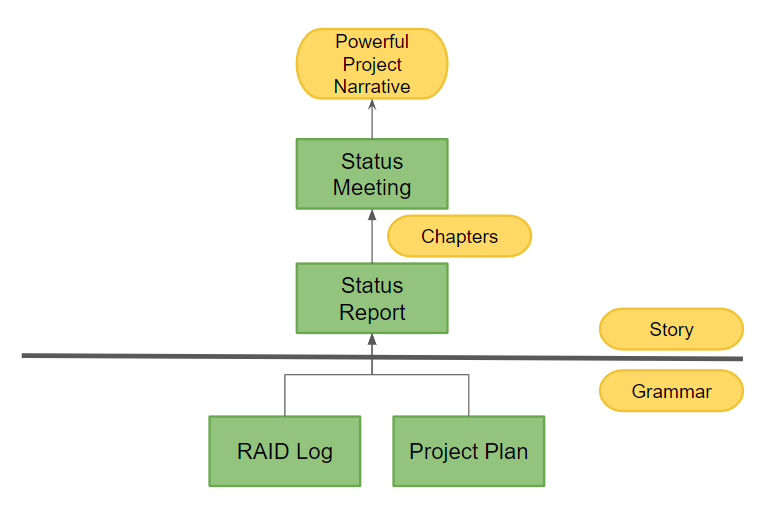

You utilise the raid log and the project plan as the grammar of your project to tell a story in chapters utilising the status report and status meeting to architect a powerful project narrative.

If I were communicating the concept in a snappy PowerPoint slide I’d use the below diagram: –

It could be suggested this is obvious, but experience tells me it isn’t. Even if the elements above are coordinated they are rarely coordinated into a powerful project narrative. They are often assembled as dry facts and disconnected across time.

We can now look at each element in turn and how to maximise its contribution and the challenges that can arise. We are going to approach it from the top down.

The role of the status meeting

There is nothing more dispiriting than a project not uitilising the status meetings to delivering a powerful project narrative as it is intrinsically linked with the stakeholders feeling the project is being effectively led.

– Ian O’Rourke, elucidateit.net

The reason it’s dispiriting? It’s likely to mean leadership of the project has been abdicated even if this is not clearly acknowledged. In order to change this it’s important to recognise the difference between progress and status.

- Progress is now, Status is the future

- Progress is facts, Status is narrative

- Progress is constant, Status has a set cadence

The above statements aren’t mutually exclusive, sometimes progress will re-assert the narrative and status meetings do contain facts but it is about the lens through which they should be framed and their purpose in the project.

The power of the leadership on the project is significantly reduced when these things are confused and the status meeting is essentially used as another form of progress update.

Progress: the factual now

Progress is about the factual now and should just be an ever-present fabric of the project. A few methods could be: –

- Constantly updating metrics supporting processes and longer tasks

- Daily emails giving progress on current or critical tasks

- Daily short check-ins to ensure no one is blocked and they are on task

The best one is metrics, this is certainly true if your project is managing a number of processes rather than just tasks as metrics can be put on those processes which represent the percentage of work at different stages in the funnel.

Status: the future narrative

The status meeting is different. It has a regular cadence rather than being continuous. It is the key tool the project manager has to demonstrate their leadership and control of the project.

The status meeting should not be focused on the factual now, as if progress reporting has been done right this should be largely understood. The focus of the status meeting should be on the future of achieving the project to plan.

This means the focus should be on: –

- Key things from the last meeting that were not achieved and their impact

- Key things to be achieved next and their contribution to success

- Risks that have arisen, their impact and mitigations

- Issues (that have ideally rotated in from previously articulated risks) and their impact

- Key things from the above that need escalation

The language used should always be a powerful, forward narrative of the journey to the end.

This status meeting should not descend into a focus on a narrow horizon of now and a litany of verbalised facts. The tone also needs to be correct. If things are going well tell this tale with a sense of verve and positivity so that can be shared. If the project is struggling switch the mood to call out the wins but also ensure the correct focus is brought to the challenges and their solutions.

Key in supporting this focus of the status meeting is the status report.

The role of the status report

The important elements of the status report are the three C’s of cadence, content and communication. We’re going to go into each in turn.

Status Report Cadence

The integrity of the status report’s cadence is very important. It’s important because these are the chapters in your powerful project narrative and these chapters should have a regular cadence, ideally, not shorter than a week being pushed to bi-weekly in extreme situations I’ve never encountered. The status meeting should also be a specific meeting, not something thrown into another structure. If your progress reporting is on the pulse of the project you’ll find a faster cadence for the status report is never asked for.

It’s also true the status report should remain tied to the cadence of the status meeting as the two should always be inextricably linked.

Status Report Content

The key content of a status report should be: –

- Overall status and statement: The overall status of the project is articulated as Red, Amber Green (and these must have a specific meaning) and the status statement.

- Achievements: A specifically selected list of wins that have been achieved since the last status report.

- Next Tasks: What needs to be focused on in the near time (with an eye to between now and the next status report) to ensure the project continues to move to a successful conclusion and to plan.

- Risks: A risk should appear on the status report if it has (1) arisen between this report and the last or (2) has become an important item of discussion for the status meeting. It should already be in the RAID log.

- Issues: Similarly issues should appear on the status report for similar reasons and already be in the Raid log. An additional factor for issues is they should ideally have already been risks.

- Metrics: Key metrics that are being used to track the project as a whole and items that are of particular focus now and as a result should be featured in the achievements and next steps.

I realise these are fairly standard entries on a status report but I needed to include them for later. What’s important is not just their presence but the active, conscious and architected rotations of the data between the sections and from the other artefacts which we cover in the third ‘C’ communication.

Let’s discuss metrics

Metrics are important on the status report but not all metrics are equal because some are only appropriate at points in time and some are just, to put it bluntly, trash. It’s important that your metrics are not open to misinterpretation or are completely superfluous. Do not just throw metrics on the report. They should all be intentional.

The best metrics to use are ones that measure processes or things that can be tracked via numbers. As an example, if you’re migrating 560 candidate applications from one OS to another in a migration project then metrics showing the application estate shrinking and how far each has progressed through the steps in the migration process are very useful, graphical and immediately engaging. A similar approach could be taken with email marketing campaigns going through a pipeline.

Surprisingly, I’m not a big fan of the overall percentage complete metric as unless you have an organisation with the right tools to do effort and resourcing really well you actually end up with what is elapsed time planning which can make percentage complete misleading without a lot of contextual factors. I understand I’m probably in a minority here.

Choose your metrics to tell the powerful project narrative accurately and engagingly.

Status Report Communication

This is the important part. The best way to view the status report is it’s a chapter in your narrative which: –

- Began when the project started

- Completes when the project ends

- Tells the story from the last chapter and leads into the next

- Elements of the status report rotate

If you do this well not only is any particular status report telling the powerful project narrative but it also allows you to re-tell the story of the project very well. The latter can be very useful as it allows questions to be answered with authority. Another way of looking at it is the institutional memory of the project governance can decay over time without using this approach.

It’s my view the status report should be constructed with this exact framing in mind and the project manager should have an eye on the overall narrative not just the contents of any particular status report.

We can show some examples of the chapter philosophy below: –

- The next steps should rotate into achievements

- Risks may rotate into being issues

- Issues rotate into next steps and achievements to address them

- Metrics are shown locked in time

- External to the status report items should be rolling in from the plan and RAID log

This process of rotation from the grammar of the project into and through the status report allows the stakeholders to see a chapter snapshot of what was being communicated on a regular cadence about the project. Not everyone may see that value immediately, but over the course of the project it will build and the project manager should be using it from the beginning.

This is very useful as other artefacts either continuously update, say metrics, or feature a lot more detail so that a snapshot is still useful.

Let’s talk about automation

I’m not against automating the status report but I am very wary of two things: –

- The amount of time it actually saves

- It can reduce the agency of the project manager

These two can result in a number of challenges.

First, the above two are related as it always seems the maximum efficiency gain of automating the status report is predicated on removing the agency of the project manager for the benefit of speed. This in turn instills the idea the project manager’s role is administrative.

Second, the agency of the project manager embedded in architecting the status report and how it feeds into the status meeting is imperative. Automation essentially flows the raw grammar of the project directly into the status report without the story or the narrative being forged by the project manager. If this agency and ability to architect those two tools is taken away the ability of the project manager to lead the project with stakeholders is severely reduced.

Third, is the potential for automated status reports to be unengaging. They become unengaging because the automation creates a propensity to produce status reports more often. This raises the challenge we’ve mentioned earlier of progress and status reporting merging. The other issue is garbage in and garbage out. Unless the sources used to automate the status report are always 100% accurate incorrect details roll in (say if the project plan isn’t current in time or tasks aren’t marked complete) which means stakeholders learn to ignore it.

This is why I think removing the project manager’s agency to architect the status report and run the status meeting to a set cadence is not worth the efficiency gain.

The role of the plan

All plans are not equal. Why they are not equal is a long list. I want to focus on three principles: –

- Dynamic

- Balanced

- Representative

These three principles are essential to your plan being part a product part of the grammar of your project.

Dynamic

It needs to be dynamic so it can be used to forecast implications, and scenario plan different approaches or issues and shifting critical paths. This means ensuring all the milestones, task groupings, predecessors, etc, build a dynamic intelligence into the plan. It becomes an analysis tool not just a schedule.

Balanced

It also needs to be balanced, specifically working at the right level of resolution to get you to your end goal. Not everything in the project should be modelled at the lowest level task. This is right sometimes but not all the time. As an example, sometimes what needs to be in the plan is the process of getting a lot of repeatable things done not all the tasks themselves and then metrics on the process should be in the progress reporting. This is because it’s the process that needs managing. Similarly, too little detail can result in loss of control so you need it to be balanced.

Representative

When people talk about the model of how the work is being executed they should be able to look at the plan and see the understood model of execution reflected in the plan in a way that is immediately understandable. This means the plan and the model of execution should be aligned, ideally, the key stakeholders’ language of understanding should be embedded in the names of things in the plan.

The plan has to be current. Plans do suffer drift due to time or being at a point of significant change but for the most part, the plan should always be accurate enough that it can be the language of what people should be focused on now and why. The more this is not true the more it gets ignored often creating a dangerous cycle.

The challenges

These three principles should just be embedded in every plan, but I’ve noticed a variety of reasons across my career as to why plans lack these principles: –

- Time can mean all the intelligence isn’t set in the plan

- Tasks are planned at the lowest level rather than at the point of control

- The focus is on immediate tasks, not the strategic view

- The plan in no way reflects how anyone else understands the work

- Organisation processes, mandates and rules limit the ability to achieve the principles

If the project plan is not flexible, balanced and representative you’ve not got a rich enough grammar in your project to help weave the powerful narrative.

An inflexible plan cannot alternate analyse scenarios so stakeholders become frustrated with alternate narratives not being easy to tell. If it’s unbalanced then the plan is micro-managing the project or providing insufficient control causing a loss of confidence. If the plan is unrepresentative it creates a cognitive dissonance with the world the stakeholders understand or it’s never accurate so it feels less relevant and stakeholders start to ignore it.

The role of the raid log

The raid log is the project artefact that everyone says they have but usually ends up being sparingly used or, even if it has some consistency of use, the risks and issues are added at different levels of quality and then not seen as living items with surrounding processes.

This is unfortunate as issues and risks account for a lot of the grammar of your project and thus the powerful project narrative. In order for it to take up this important place the raid log should: –

- Be constantly updated with new issues and risks

- See the risks and issues as living entities that are updated until closed

- Have a common structure for how an issue or risk is described

- Have regular meetings where issues and risks are reviewed

- Rotate its contents up through the status report into the powerful project narrative

A key thing I learned on a large IT-enabled change project is to insist your risks and issues are all articulated with a common pattern. This has three advantages: –

- Everyone who writes a risk or issue into the log articulates them in the same way

- They are all entered at the same quality level

- They constantly appear in the status report in the same pattern

An example of a pattern for an issue might be: –

The issue is <insert description> caused by <insert cause> and the consequences are <insert consequences>. The options are <insert options>.

This means each item in the log is robust and isn’t littered with some description that has been hastily dropped into the log. This enriches the grammar of the project as each item in the log is more complete and actionable and every item rotates to the status report utilising the same structure rather than appearing as random statements or declarations.

The Conclusion

It’s my view to demonstrate leadership of a project and to maximise success it’s important to weave a powerful project narrative over the course of the project. This needs to be achieved through the project having a rich grammar to be found in foundational artefacts like the plan and the raid log which can tell a story that the projects manager decides how to tell as a narrative via the status reports and status updates.

It’s important for the project manager to have the ability and space to architect this narrative and be able to retell it over time to maximise engagement and allow the stakeholders to be protagonists in this story. Failure to do this results in the project being disconnected facts and governance having a short institutional memory. It can also result in leadership being replaced with administration which means it can feel like or actually is the case that leadership has been abdicated.

There are many reasons why the powerful project narrative isn’t told, but we should rise to the challenge to bring it to the surface.